As we

cross the threshold into a burgeoning dystopian tomorrow and pause at the edge of the steepest precipice of that dreaded, unfathomable hereafter, braced for the

worst, it's best we prepare for whatever untoward scenarios might come our way.

While the imbecilic new leader of the free world and de facto tyrant-in-training prepares to deregulate industry, dismantle the EPA (and the FDA), and ramp up international tensions, it’s a fair guess that if our complete decimation of the environment doesn’t get us, our escalating capacity to murder on a grand scale will. Sure, we can keep our chins up and our resolve strong, and try to remain positive—but all that and a can of soup will leave you hungry.

While the imbecilic new leader of the free world and de facto tyrant-in-training prepares to deregulate industry, dismantle the EPA (and the FDA), and ramp up international tensions, it’s a fair guess that if our complete decimation of the environment doesn’t get us, our escalating capacity to murder on a grand scale will. Sure, we can keep our chins up and our resolve strong, and try to remain positive—but all that and a can of soup will leave you hungry.

So let us take a moment and have a look at one possible worst-case scenario, as indelibly related by the cataclysmic made-for-BBC sonic death knell from 1984,

THREADS.

It's all played out very matter-of-fact, and with no music or sermonizing to skew emotions, its decidedly sober, quasi-documentary approach lets the viewer know early on that as things go from bad to worse, the stoic, unflinching THREADS will offer no spiritual reprieves.

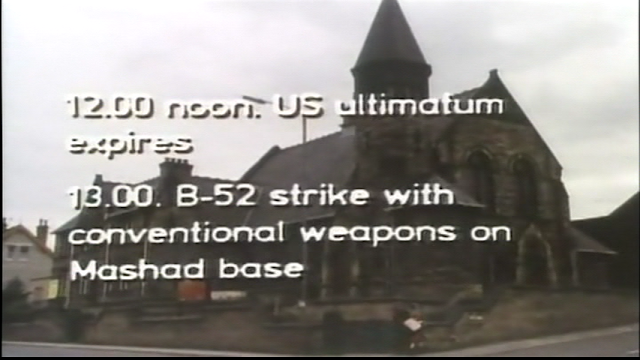

After weeks of rising tensions due to an alleged U.S.-backed coup in Iran, Russian troops cross its northern border, which prompts the U.S. to send its own soldiers to protect the much-coveted oil fields. (familiar?) When an American nuclear submarine disappears in the Persian Gulf and the mounting evidence points to Soviet involvement, an irreversible course is set.

From its

opening moments, it is quite clear that THREADS is playing by its own set of

rules and was created to deliver one message only: mankind is heading in a very bad

direction and if we continue, there will be apocalyptic results. Concisely written by Barry Hines (and directed by Mick Jackson), it’s a dire warning steeped deeply in the

anti-nuke rhetoric of the mid-1980’s. But to a troubled world that has

learned so very little in the ensuing years, it’s just as relevant as ever.

As THREADS begins, we're introduced to a pair of young lovers, Jimmy Kemp (Reece Dinsdale) and Ruth Beckett (Karen Meagher), and through them their parents and siblings. And as they all go about their day-to-day existence in gritty, industrial Sheffield, England, a foreboding, escalating international crisis plays out in the newspapers and on the TV sets and radios which speckle the backdrop.

It's all played out very matter-of-fact, and with no music or sermonizing to skew emotions, its decidedly sober, quasi-documentary approach lets the viewer know early on that as things go from bad to worse, the stoic, unflinching THREADS will offer no spiritual reprieves.

Throughout THREADS, detailed lists of logistics, scientific analysis and hypotheses unspool onscreen, offering rare insight into the numbers and probabilities of an ensuing nuclear war. Early on, we learn that Sheffield, already an industrial target, is also only 17 miles from the nearest military target, an RAF base.

As we get to meet and know the Kemp and Beckett families, respectively, there is a growing sense that their stories are not the story, but rather just further detail in a singularly grim cinematic tapestry. With very little in the way of traditional character motivation or individual conflict, it's as if we're being set up to watch lab rats respond to some awful trauma. THREADS goes about the forbidding, untidy business of disassembling our civilization with a cold, uncompromising candor necessary to compel its audience to action. It is a message of certain, utter doom, meant to entertain nobody.

At the bar, now weeks into the growing crisis, Ruth tells Jimmy she's pregnant. "It's not the end of the world." It's all handled rather perfunctorily, with Jimmy, hesitant at first, deciding it best they marry, and the two families getting together over dinner to hash it all out.

But as the young couple begins setting up house in a new apartment, the crisis reaches its boiling point.

Soon after, we meet yet a third group of characters, the Sheffield Emergency Response team, which convenes in a basement office and begins pondering the worst.

And then...

It isn't simply the graphic realism I refer to. After the bombs fall (210 total megatons on the UK alone), all that remains on the other side of that equation is endless suffering, hunger and hopelessness.

I had initially planned to focus much of my attention on the implacable force of the second half of THREADS, if only because the anti-nuke movement which propelled this essential film to fruition has all but ceased. But I feel this prolonged dirge through hell has already spoken its heart and mind and much further dwelling on this subject will do me no good whatsoever. Just a couple of moments remain that I would like to leave you with.

After the bombs have their way with Sheffield, Jimmy Kemp's parents hide behind a makeshift shelter (a kitchen door) for what seems like days, too sick and weak and injured to muster much more than occasional muted cries of anguish and vomiting.

Like most of which follows, it is a scene of total despair, and one can only hope their suffering will end soon. But Mrs. Kemp, badly burned and aware that her time is limited, becomes determined to look for Jimmy's little brother, who was nearby during the blast. And so husband and wife set out, shambling—and then on hands and knees—to find their boy.

And the fires rage on all around them.

And Mrs. Kemp, in a crawl, spots a shoe. His shoe. He's buried in rubble, but at least the boy was spared a worse fate.

Sobbing weakly yet without respite, it takes all but her last shred of energy to hoist herself forward so she can grab hold and kiss the last piece of her boy she'll ever see, his sneaker.

Across town, the Beckett's have fared a bit better using their basement as a shelter. Of course, the fallout has made everyone ill, regardless.

And Ruth Beckett, too distraught for food, responds in kind when her mother insists she eat for her unborn child's sake. "I don't care about this baby anymore!"

After her grandmother dies and the three remaining Becketts drag the body upstairs, a despondent Ruth wanders off into the streets, perhaps looking for Jimmy, though seemingly aimless.

Through a haze of toxic smoke and fallout, she plods tentatively onward, from one awful scene to the next, a reluctant arrival to hell.

When a hysterical young boy approaches her screaming for his mother, eyes bulging psychosis, she regards him briefly but keeps pressing forward.

During this excursion, it becomes clear that the lucky ones are already dead. The survivors, for however long they may last, are either terribly burned or sick or injured, with many having simply gone mad.

The entire movie, uncut, if you can ignore the Italian subtitles.

As we get to meet and know the Kemp and Beckett families, respectively, there is a growing sense that their stories are not the story, but rather just further detail in a singularly grim cinematic tapestry. With very little in the way of traditional character motivation or individual conflict, it's as if we're being set up to watch lab rats respond to some awful trauma. THREADS goes about the forbidding, untidy business of disassembling our civilization with a cold, uncompromising candor necessary to compel its audience to action. It is a message of certain, utter doom, meant to entertain nobody.

At the bar, now weeks into the growing crisis, Ruth tells Jimmy she's pregnant. "It's not the end of the world." It's all handled rather perfunctorily, with Jimmy, hesitant at first, deciding it best they marry, and the two families getting together over dinner to hash it all out.

But as the young couple begins setting up house in a new apartment, the crisis reaches its boiling point.

Soon after, we meet yet a third group of characters, the Sheffield Emergency Response team, which convenes in a basement office and begins pondering the worst.

And then...

It isn't simply the graphic realism I refer to. After the bombs fall (210 total megatons on the UK alone), all that remains on the other side of that equation is endless suffering, hunger and hopelessness.

I had initially planned to focus much of my attention on the implacable force of the second half of THREADS, if only because the anti-nuke movement which propelled this essential film to fruition has all but ceased. But I feel this prolonged dirge through hell has already spoken its heart and mind and much further dwelling on this subject will do me no good whatsoever. Just a couple of moments remain that I would like to leave you with.

After the bombs have their way with Sheffield, Jimmy Kemp's parents hide behind a makeshift shelter (a kitchen door) for what seems like days, too sick and weak and injured to muster much more than occasional muted cries of anguish and vomiting.

And the fires rage on all around them.

And Mrs. Kemp, in a crawl, spots a shoe. His shoe. He's buried in rubble, but at least the boy was spared a worse fate.

Sobbing weakly yet without respite, it takes all but her last shred of energy to hoist herself forward so she can grab hold and kiss the last piece of her boy she'll ever see, his sneaker.

Across town, the Beckett's have fared a bit better using their basement as a shelter. Of course, the fallout has made everyone ill, regardless.

And Ruth Beckett, too distraught for food, responds in kind when her mother insists she eat for her unborn child's sake. "I don't care about this baby anymore!"

Through a haze of toxic smoke and fallout, she plods tentatively onward, from one awful scene to the next, a reluctant arrival to hell.

When a hysterical young boy approaches her screaming for his mother, eyes bulging psychosis, she regards him briefly but keeps pressing forward.

During this excursion, it becomes clear that the lucky ones are already dead. The survivors, for however long they may last, are either terribly burned or sick or injured, with many having simply gone mad.

By the end of her tour, Ruth is not quite the same

woman. As she approaches a mother holding

a baby—a charred, lifeless baby—Ruth has already emotionally run the gamut and

seems incapable of being shocked. And so all she can manage is to return the

woman's cold, barren stare.

The entire movie, uncut, if you can ignore the Italian subtitles.